A movement to ban disposable plastic straws is sweeping the US after gaining traction in cities and countries across the world, finding widespread attention after Starbucks announced it would phase out disposable straws by 2020. However, according to disability rights advocates, banning disposable plastic straws, which were originally created as disability aides, presents unacceptable barriers for people with many disabilities. Aided by a widespread desire for meaningful environmental change and a viral video of a sea turtle with a plastic straw stuck in its nose, plastic straw bans have been celebrated by individuals, companies, and legislators as a positive and necessary move towards widespread environmental change. But do plastic straw bans really represent meaningful change—and if so, at what cost? According to those affected and a growing pool of evidence, plastic straw bans not only fail to accommodate people with various disabilities, they also fail to create the meaningful positive environmental change they claim to prioritize.

The Numbers

Straw bans have been framed by many as a necessary first step toward reducing rid of plastic waste, and even those who acknowledge the challenges plastic straw bans present to elderly and disabled individuals have framed straw bans as a choice between access and the environment. But it’s important to consider the numbers when thinking about those impacts.

How much do disposable plastic straws really contribute to the world’s plastic waste and overall pollution? According to a recent report by environmental group Better Alternatives Now (BAN), plastic straws and stirrers (grouped together in this report but not in all bans) comprised about 7% of plastic items found along the California coastline, by piece. Compared to plastic bags at 9% or plastic bottle caps at 17%, it’s a not-insignificant chunk of plastic. However, when taken by weight, a report by Jambeck Research Group places plastic straws at only .03% of aggregate plastic in the oceans themselves, suggesting that straws’ lightness and buoyancy lead them to end up overrepresented on the coastline.

Perhaps even more saliently, a recent survey by Ocean Cleanup estimated that nearly half of the plastic waste found in the oceans’ largest garbage patch comes from fishing nets, primarily commercial ones. These numbers point to what disability rights advocates have said about straw bans: while the bans have enormous potential to harm the elderly and disabled, they bring about neither the dramatic reductions in plastic that curtailing activities of corporate polluters would effect, nor the smaller yet harmless reductions that bans on items like plastic balloons and plastic shopping bags bring about.

Also significant to note about the BAN report is that products labeled as biodegradable or compostable plastics are not, in fact, actually biodegradable in an earth or ocean environment. Many are moving toward biodegradable plastic straws as a substitute for current plastic models, but according to data, those not only do not come with any actual impact on ocean plastics, they also bring additional challenges of potentially fatal food allergies and reduced durability into the lives of disabled straw-users.

Another salient point many have made is that plastic conservation efforts have many other starting points that don’t target accessibility aides. Plastic straws were chosen as a symbolic starting point by environmental advocacy group Lonely Whale (originator of the #stopsucking social media campaign), who have acknowledged in multiple interviews that straw bans present potential problems for people with disabilities. Lonely Whale did not respond to my request before press time—a statement from the group has been added to the end of this article*—but resources including the group’s staff training .pdf clearly outline the need for acknowledging the complex issue straw bans present to disability rights.

Kim Sauder, a Toronto-based disability rights advocate and PhD student in Disability Studies, wants people to recognize that they aren’t choosing between disability access and the environment. “That legitimizes the idea that a straw ban will achieve something. It ignores the reality that a straw ban won’t do what legislators say it will. The ‘conversation’ they are starting really boils down to what people will accept as success and the harms they will justify in the name of that.” According to Sauder, many who have pushed for straw bans appear to be totally okay with what even its biggest champions deem a symbolic victory against pollution, even when it comes at the very real expense of disability access.

Potential for Harm

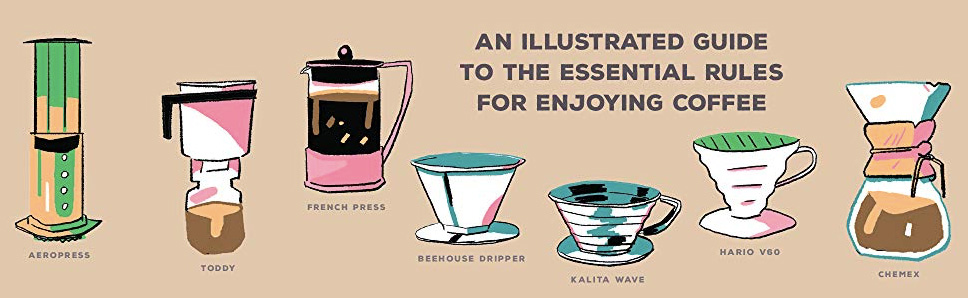

While plastic straws have become a go-to for all types of customers in cafes, bars, and restaurants, they were originally invented as a disability aid and used in hospitals. Joseph B. Friedman created and sold the first disposable bendy straws as a tool to help reclined patients, as well as people with assorted other disabilities, drink easily from cups. Sold as the Flex-Straw, they were and still are an inexpensive, temperature-resistant, sturdy, and sanitary alternative to the reusable silicone feeding tubes which were in heavy rotation before their advent. They achieved mainstream popularity because the design was superior to existing alternatives for all people, not just people with disabilities.

As disability rights advocates have pointed out, all current substitutes fail to meet the same standard of universal design. Compostable alternatives lack the same sturdiness, making them too easy to chew through or choke on for people with limited jaw mobility and (in the case of paper straws) too flimsy for people with longer drinking periods. Reusable alternatives present problems too; not only would people with disabilities need to carry them around on top of other medical necessities, they’re also difficult to wash, dangerously unsanitary if not properly washed, conduct heat and cold, and present cutting risks. With the current selections of alternatives on the market, if establishments don’t have a stash of plastic straws in-house, they risk creating situations where people with specific disabilities either can’t drink safely, or can’t drink at all.

“Plastic bendy straws provide me with a basic needs that everyone else has access to,” says Jae Kim, a straw-user and social work intern at Seattle’s Arc of King County. “They became a part of me that I can’t lose. Without them, I can’t consume any liquids and it is the biggest, scariest concern I have.”

Sauder argues that it’s the responsibility of legislators and straw manufacturers to ensure that they create a truly viable alternative that works for all before banning the disposable plastic options that currently serve everyone’s needs, pointing out that it shouldn’t be on people with disabilities to lose essential access tools in order to support symbolic legislation. Kim wants non-disabled people to think about how that experience would feel. “How would your life look if you needed to go through barriers just to have a sip of water?”

Case Studies: Seattle, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara

Many governments implementing straw bans have built in disability exemptions, but those too can present serious problems if not worded correctly. In order to make sure that people who need plastic straws can access them, laws need to include clauses that specifically mandate keeping plastic straws in-house with signage to let people know about they’re available, rather than simply exempting businesses who want to accommodate disabled patrons.

The first US city to pass straw ban legislation was Seattle, where the legislation passed with an disability exemption that was widely criticized for not being stronger. According to Seattle Disability Commission co-chair Shaun Bickley, Seattle Public Utilities failed to reach out to the Disability Commission for feedback prior to passing the legislation, and then passed a ban with an exemption that allowed—but did not require—businesses to serve flexible plastic straws to patrons with disabilities. Last week, in light of the many voices drawing attention to the issues with the exemption, they issued a statement to “food packaging and serviceware stakeholders” detailing the new legislation as well as emphasizing that “SPU provides the above listed exemption and also encourages food service businesses to keep a supply of flexible plastic straws available for customers with a physical or medical condition. We would appreciate if distributors and associations would inform your customers and members of this exemption and to share our encouragement that they maintain a supply of flexible plastic straws for this purpose.”

San Francisco also passed straw ban legislation with a disability exemption stipulating that businesses are allowed to make exemptions for people who need them, rather than mandating that they accommodate people with disabilities. This was criticized by many in the disabled community because, as proven with countless ADA requirements, many businesses accommodate people with disabilities only when required by law. According to Supervisor Katy Tang, the legislation is currently being amended to include more specific language around disability access.

“Legislation does not typically spell out every detail for implementation. The intent behind our originally included a clause regarding the disabilities community is that restaurants/retailers would indeed need to have some plastic straws on hand for those who request them due to a medical reason,” Tang told me via email. “The ADA is broad enough in that all places of public accommodation should be making reasonable efforts to accommodate those with disabilities in every way possible.”

Much more extreme is the legislation introduced in Santa Barbara, which not only prohibits any business or individual from handing out plastic straws—including compostable plastic straws, which are the closest alternative for people who need to use straws due to disability—it actually punishes repeat offenders with heavy fines and jail time. For providers to get a disability exemption, they must apply to the city of Santa Barbara for an exemption due to “medical necessity,” an extra step that makes it that much harder and more expensive for businesses to serve customers with disabilities. I have not been able to get comments from anyone involved in the Santa Barbara legislation.

Legislation aside, owner of Washington’s One Cup Coffee Tonia Hume plans to make sure her patrons with disabilities have everything they need to have a positive experience. Hearing rumors of the impending straw ban, Hume swapped the plastic straws at her four locations for biodegradable plastic straws; once the ban passed, she learned of the issues people with various disabilities were expressing and is now committed to making sure they’re able to access her space just as easily as before. “We had plastic straws that didn’t bend before, so making the swap to compostable was no big deal,” she said. Once she found out that bendy straws were crucial to many, she committed to making sure they’re available in all locations at all times. “You want to be a place that’s welcoming to everybody,” she said.

San Francisco’s Wrecking Ball Coffee also announced that in light of the ban, they will now carry two types of straws, with a request that patrons use compostable straws unless they need plastic bendy straws. “We were always proud that we had compostable straws at WB, but when SF began discussing a plastic straw ban, we looked a little deeper,” Wrecking Ball co-founder Trish Rothgeb told me by email. Hearing the voices of the disabled community, they added plastic bendy straws to their condiment bar. “It’s not up to the baristas to police the situation. We can’t assume we know a person’s needs by looking at them. Will a kid get a straw because it’s fun, when it’s really not meant for them? Most probably, but it’s a small price to pay for making sure every guest gets what they need without any judgement or extra work on their part.”

What You Can Do

Whether you live in a place with a straw ban or not, there’s a lot you can do, both for the environment and for people with disabilities that will be affected by straw bans.

If you live in an area with a straw ban and own, manage, or work in a business that serves beverages, make sure to keep a stash of plastic bendy straws for patrons with disabilities that need them—ideally right in the condiment area with adequate signage, like Wrecking Ball now does. If you live in an area that is pushing for a straw ban, contact your legislators and fight for a disability accommodation mandate, rather than just an exemption.

In addition, if you’re a non-disabled person who wants to help the environment, do what you can to take personal responsibility for your own use of reusable and sustainable materials for as many of your daily activities as possible. “Are you cognitive of the environmental impact you may contribute in all aspects of life,” asks organizer and Seattle Disability Commission chair Khazm Kogita. “How can you strive to minimize your footprint on the planet? At the same time, be aware that different people have different needs, and for some people, straws are an essential part of their daily living. Are your actions or decisions hindering other people’s independence?”

Most of all, listen to people with disabilities when they raise issues and recognize that they understand their bodies and accessibility needs. Coffee shops have long been spaces where people congregate to challenge the status quo, and as such, they are uniquely equipped to make sure the fight against plastic waste prioritizes the needs of people with disabilities.

RJ Joseph (@RJ_Sproseph) is a Sprudge staff writer, publisher of Queer Cup, and coffee professional based in the Bay Area. Read more RJ Joseph on Sprudge Media Network.

Top image © dark_blade / Adobe Stock.

*Correction: An earlier version of this article unintentionally misrepresented Lonely Whale’s position on disability rights in relation to the group’s straw ban campaign. Sprudge regrets the error, and the paragraph in question has been updated. In addition, below please find a statement from Lonely Whale, received after this story was originally published:

Lonely Whale’s movement For A #StrawlessOcean has worked to advocate for the needs of those in the disability community who require a straw to drink. We are committed to working with the disability community to ensure that voluntary adoption of our campaign is inclusive, to identify plastic straw alternatives that work for everyone, and to make these alternatives are readily available at any establishment. We believe that with thoughtful dialogue between environmental and disability communities we can address the growing plastic pollution crisis without compromising the needs of the disability community. We welcome the opportunity to speak further with those who represent the disability community at large to ensure any opportunity we have to advocate for more inclusive policy language proposed by cities, counties and states and voluntary change in response to our campaigns protect the accessibility rights for those within the disability community.

—statement from Lonely Whale.